Field Reports

Note: Lately I've been returning to the habit of writing prepared remarks in an effort to stick to the strict time limits of various events. As an added bonus, this means I end up with a transcript that can be posted with relative ease. Below is one such example, originally presented at the World Design Forum (previously mentioned here) on October 19th in Eindhoven and curated by the indefatigable intellect of John Thackara. Attentive readers will notice that the starting point shares something with an earlier post, but it quickly diverges. And so...

I'm an optimistic enough to believe that humanity will find a way to weather the immense and multiple crises that are mounting today. I'm less optimistic for our institutions, however, and this is why I've chosen to practice design inside a government agency. I believe that our institutions are outdated technology and that the tools and attitudes of design are part of the fix.

At Sitra we've been testing this notion since 2009 with Helsinki Design Lab. We have projects at different scales, from 10s of thousands of euros to tens of millions.

On the small end, that includes projects like Open Kitchen, which is a bootcamp for food entrepreneurs. We've had an explosion of pop-ups thanks to Restaurant Day, a festival that happens 4 times a year which you can see an image of here.

But what pops up inevitably pops down. Open Kitchen is designed to fill a missing rung on the ladder of innovation. In doing so we hope to help restauranteurs move from pop-up to permanence. This is important because we want to combine the faster cycle speed of pop-up innovation with the reliability of everyday businesses.

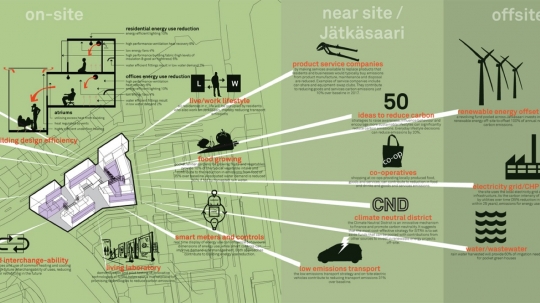

On the bigger end of the spectrum, we do things like Low2No, a sustainable urban development project that looks like a block of 5 buildings, but it's actually a vehicle to work with the ministries, the city, and private developers to create climate friendly regulations and business models. We use the messy reality and imperative of the construction project to bring urgency to regulatory change.

One early success has been a change to the fire codes to make it legal to build large buildings out of timber—something we had never expected when we began but discovered and acted on along the way. We call it a success because 4 other timber buildings have been announced since the change, so this is early but important evidence of scale.

What links both of these is an interest in using tangible projects to help organizations, as Jan Van Der Kruis noted earlier, to "witness change."

We have not designed roads to have traffic jams, hospitals to have queues, services to remove personal agency, and tax forms to be confusing. Institutions and their procedures can appear immutable and static, but they are nothing more than an accumulation of human choices. We can make difference choices today, and have different institutions tomorrow.

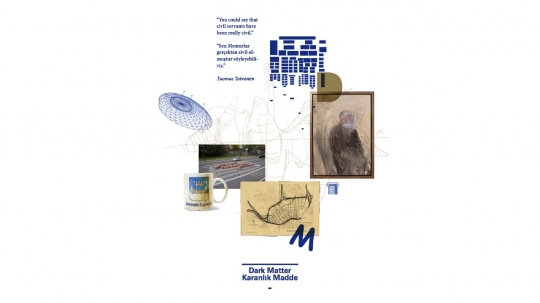

To do so, we need to develop ways to grapple with something that Dutch architectural historian Wouter Vanstiphout calls "Dark Matter". It's a metaphor for the complexity of institutions: all of the invisible things like incentives, pay grades, organizational culture, and other issues that nevertheless shape an institution's interactions, behavior, and output.

Dark matter is not a barrier because it's massive or negative. Rather it impedes change because it is inscrutable and opaque. We use our projects to help us find the texture and grain of dark matter, and in doing so find specific opportunities for change at the systemic level.

Let me switch now and share a bit of recent history in Helsinki, which nicely explains the imperative for another of our projects.

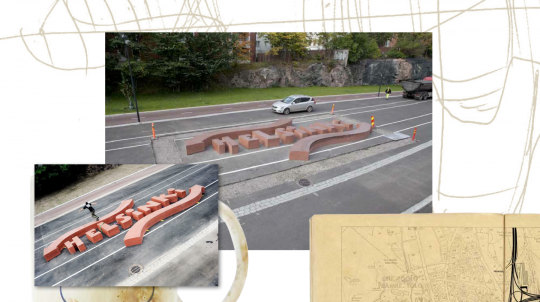

This is part of a cargo freight line in Helsinki that was renovated into a recreational path earlier this year. It was designed for skaters and it opened on June 12th. Exactly 3 months after it opened, the city of Helsinki came back and vandalized their own work by digging a moat around it to prevent skating. This was done in response to complaints by citizens who live nearby.

One week later, on September 17th, the city came back and filled in their moat after other citizens complained about losing the skate park. By the way, the original project passed through all of the required due process. The city built the thing, defaced it, then restored it, all within a span of four months.

Why?

Because the city was responsive to its citizens —and quickly! But responding in a series of transactions is not the same as fostering an inclusive debate about how we want to live together. Technocratic silos can only respond with technocratic answers. Why not a sign with hours, for instance? Because public works only have trucks and shovels!

Ascriptions of incompetence would be too easy, too simplictic. Instead we find that the institution itself is not in a fair fight with today's society. We are connected through fast and agile networks. We expect engagement from those we take the time to interact with. We want to contribute, not just receive.

But our institutions are without inboxes. In most western countries we have a democratic right to say NOT IN MY BACKYARD, but how easy is it to say YES?

In Helsinki this dynamic is summed up rather poetically in the official portrait of a recent Director of City Works, seen here, seemingly without a face. One wonders if the metaphor was lost on them. And although this is from Helsinki, it's a useful emblem for many institutions in many places, I would guess.

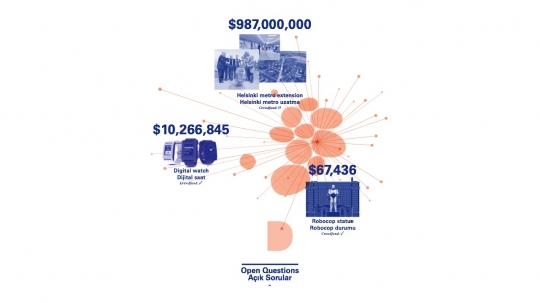

At the same moment we see experiments on the fringe. Crowdfunding websites are providing an alternative for citizens to financially say YES IN MY BACK YARD. This potentially solves a funding problem but it skips questions of democratic process, of debate. One of the first spatial projects on the US crowdfunding site Kickstater was a robocop statue for Detroit. While I happen to like the project, who am I, living in Helsinki, to say that this is what Detroit needs? The local and the global collide in this example with no clear answers just yet. We will have to design one together.

The cost of interacting with institutions is so high that citizens increasingly prefer to accept the risks of self-organization. As our culture changes, the public sector will continue to find itself subject to competition in ways that it's not used to. Restaurant day, which I showed earlier, was organized on Facebook … inspired by the difficulty of the city's own formal permit procedures. This is an unexpected, asymmetric competition to be sure!

If we expect our municipalities and our ministries to behave differently, they will need new capacities as well.

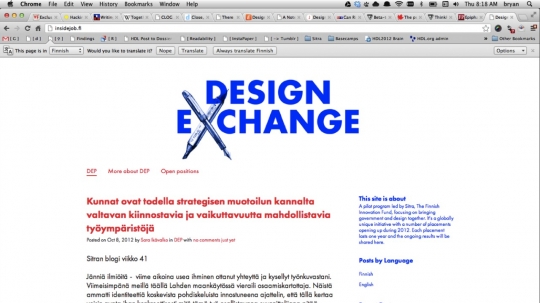

In the Design Exchange we help governments recruit and host designers as part of existing project teams. In other words, we help government change its people, and therefore its tools. These individuals are employees, not contractors. They're part of the fabric of the organization.

By being on the inside, they are better positioned to help frame questions in a holistic way from the beginning. This happens both by bringing a human-centered perspective; by enabling new forms of more fluid communications between institutions and citizens; and by making co-creation with citizens a basic tool, rather than an exceptional one.

Rosanne Haggerty, who runs an NGO in the US aimed at ending homelessness, once told me that "people have a hard time accepting failure unless they also see a solution." With these projects we're attempting to manifest solutions promising enough that they help us engage the failures of the status quo.

Thinking about it today, our hypothesis with the Design Exchange and the other projects is that by jumping straight to possible solutions, and by doing that close to government, we can begin to have a more articulate conversation about how we will redesign our institutions from the inside out.

Thank you.

Jesper Christiansen of MindLab and Laura Bunt of Nesta recently published an excellent paper entitled Innovation in Policy: allowing for creativity, social complexity, and uncertainty in public governance. I enjoyed reading a draft of the paper and acting as a respondent, both through a chain of emails as well as offering some remarks at a small seminar held at MindLab in Copenhagen. For more background on the paper, Laura's blog post is also relevant.

My full remarks are available on the MindLab blog. But to spark your interest, I'll give you a taste that ends with a riddle:

I agree that we are beset by crises, but I’m optimistic enough to expect that humanity will weather them relatively unscathed as individuals, families, and communities. The question is whether our institutions will be as lucky.

I’d like to begin with a riddle. What binds together the following…?

- A pop-up restaurant

- A Private school

- A Riot

- An Email

To find out, hop over to the MindLab blog!

If you look closely, you’ll see many of the rooftops of Bucharests’ Lipscani quarter glimmer in the sun, reflecting newly applied copper and tin back to the sky above as if to suggest that first and foremost this metropolis is rebuilding itself under the eyes of god. While this city is indeed dotted with its fair share of sites bearing religious importance, there’s no mistaking the zeal with which modern Bucharest is being rebuilt by the people on the ground. It’s a place where one encounters making and re-making almost at every turn and it's a great coincidence that the neighborhood at the forefront of this change is one with a long history of trades and guilds. Romania is not waiting for any heavenly bodies to anoint them, if the organizers of Connection have anything to say about it the focus here is on linking up the market and the citizenry into a society that is sustaining and sustainable. I’ve come here to keynote Connection, a conference on social innovation put on by an ambitious group called Ropot. More on this in a bit, but first: the city.

Lipscani plays the part of a familiar European tourist district, replete with terraces sponsored by beer companies, street vendors, and the steady thump-thump of Euro beats oozing out of cafes with more neon than customers. On the surface it can be generic, but with a closer look one finds moments of genuine and endearing locality. Many of the wares on offer at the street market, for instance, appear locally produced and this includes the sweets (which are very sweet). Pockets of the 19th century, such as the popular brewery restaurant Caru' cu Bere offer a hospitable glimpse of the pre-communist city, not to mention a hearty meal to beat back the chill of an autumn Sunday.

A local wedding amidst the tourists that fill Caru' cu Bere to the rafters

According to locals, the original dream of the reinvigoration of this neighborhood was to create an artists’ quarter. Although the current iteration is more gentrified than this—and it’s no Postdamer Platz, so this gentrification is very relative—gems like the small bar Atelier Mecanic shine through. It’s a sort of high style junkyard where the local cool kids drink amidst a setting various mechanical trinkets repurposed as thoughtful decoration. The communist-era leftovers lining the walls are strong material symbols and it’s tempting to see them as trophies of the conquest, now drained of their robotic animation and relegated to watch from their perch on the walls as contemporary Bucharest thrives. It’s the kind of place where one imagines a new generation of intelligentsia congregating, like the editorial staff of Decat o Revista, an upcoming local magazine on the model of “Wired meets the New Yorker”, or the group of architecture students sketching across a narrow table while I visited.

Sunday afternoon in Atelier Mecanic

But one does not come to Romania without thinking about Dracula, and so to his castle we go. Three hours north of Bucharest is the town of Bran, the population of which has just grown by 80 for Connection, a long weekend focused on building social innovation capacity within central eastern Europe. Initiated by the enthusiastic four-person core of Ropot and executed with a network of partners, the event brings together a wide range of people from Romania and neighboring countries to bring new ideas to the conversation. Carefully crafted as a multi-day event, it’s also designed to build connections and spread knowledge laterally.

Don't let the looks fool you, although the atmosphere was decidedly relaxed, Connection was carefully orchestrated

Blindly-drawn portraits posted as a who's-who of the event

In the spirit of the many social entrepreneurs in attendance, I came to make a simple pitch: details make or break big picture ambition, and design approaches are a useful lens to pursue the details and the big picture concurrently. Under this umbrella I took the opportunity to share Sitra’s work on projects including HDL, Synergize Finland, and Low2No. The latter containing an excellent example of the big picture/small detail balance in Sitra’s efforts to remove barriers to large scale timber construction in Finland. This is driven by the big picture goal of a carbon neutral built environment but involves to specific (but unexpected) actions such as working to change fire codes so that large scale timber construction is possible, not just for us but for others as well.

But I started my talk with a simple observation from the streets of Lipscani: we live in a world of multiple overlapping systems and yet these are all too often sub-optimized in isolation of each other. In just about any European city you can observe this for yourself in very concrete terms by paying attention to the downspouts. Often you will find that downspouts and other external plumbing takes a less than direct path to the ground, and occasionally one that involves significant conflict, such as the photo above with a drain violently puncturing through the decorative plaster work of the building. This is a visible symptom of the architect and plumber not agreeing on which system will take precedence and which will gracefully defer.

The rigidity of different systems becomes extremely apparent in moments of forced intersection

It’s an example of the impossibility of agreeing to disagree when decisions are involved. We can agree to disagree on a philosophical basis because this stays in our minds, but when it comes time to do something in a world of finite space, time, and material, action requires agreement—or violence.

Function piercing decoration, or: the hard considerations of gravity, flow rates of water within a pipe, and the threat of water damage against the soft factors of the cultural value architectural form, symbolic meaning of a building, and connotations that a physical structure conveys onto the organization that sits within it

At the core of this observation, and my pitch that design is positioned as a lens to help us make sense of it as a practice, is the observation that we’re still often clumsy in bringing synthesis to hard and soft factors. In the example above, rain water, flow rates, gravity, etc. vs. architectural form, cultural meaning, social connotations.

To resolve these two into a harmonious whole, as one is able to observe in more considered acts of architecture, requires a synthetic approach that balances the demands of hard and soft factors. This is something that the best businesses do as well. Nokia had touch screen phones much before Apple, after all, but the technocratic approach they took to conceptualizing a phone as a gadget inhibited full consideration of the softer side of the cultural role of a cellular phone. (For what it’s worth, this is demonstrably different now that Nokia Design is under the leadership of Marko Ahtisaari).

And so one of the central aspects of the conversation at Connection was the difficulty of bringing hard economic costs and soft social benefits onto the same ledger so that an attractive investment case can be made to appropriate investors. As groups across Europe are currently struggling with this issue, I was not surprised to see the same here in Romania. What encouraged me, however, was the verve with which some of the attendees took up the challenge.

As groups which aspire to support and enhance local communities increasingly look to social investment rather than grants, an important bit of mindset change is occurring. The more we as a society are able to entertain social returns on investment the closer we are to obtaining one of the basic mechanisms of a healthy social society—one that neither forces each individual to be a self-sufficient island nor forces the state to make unrealistic promises.

Investments come with investors, and investors have a moral obligation to put their money to best use. In the past this has more often than not implied the best annual return in financial terms. Looking forward, the notion of returns will slowly become more open, perhaps also including social returns expressed in monetary equivalent in a manner similar the cap and trade of carbon emissions.

The reason why I gave up my weekend to participate in an event in the middle of Romania is because I wanted to see how this part of the world was thinking through these issues, and what I might be able to bring back with me to our work in Finland. There are a handful of leads I will be following up, but the thing that came through most clearly was the drive and commitment of the participants to devise new ways of addressing the issues they’re concerned about—be it corruption, poverty, social exclusion—with a constructive eye towards the future. Connection itself is a testament to that by virtue of the fact that it eschews the typical conference format of individual grandstanding and hands-off consumption of presentations and instead delivers a weekend of capacity building.

Romania's native carmaker, Dacia

We took turns sharing experiences in finding the right product, developing a business case, and what to look for in policy EU developments that will affect social innovation. But also about very pragmatic skills and tools such as learning how to hone a pitch and how to skillfully use media—both traditional and non. These how-tos were anchored by a mix of stories on the ground from individuals such as Chris Worman who is developing an innovative community ‘loyalty card’ scheme in central Romania and Dr. Anna Burtea who is exploring new commercial opportunities to enhance her foundation’s reach and impact. As examples of social innovation in development they were not all easy-breezy success, and that’s what I appreciated most. The Connection team managed to create an environment where frustration and failures were just as much a part of the conversation as success and scale.

Ropot and their co-organizers take a moment to regroup and adjust plans for the next session

So when I write that I left the event feeling optimistic it’s for the same reasons that I enjoyed my brief time traveling the landscape of Romania: it’s a place that is still in the habit of making things, but equally one that can remake and repair when needed. Perhaps because of the relatively high levels of contrast visible even on the street—I did, I must confess, nearly escape a pack of angry wild dogs—I detected in my fellow attendees both a shared sense of responsibility for the future as well as an imperative to find one’s own specific contribution.

Back in Bucharest, as I type this blog post I am using a wifi network with the password “2030wifi”. An eye on the future, indeed.

This post continues the story of Seungho’s trip to Cambodia with Aalto University. Read the first part if you want to catch up...

So here we were, nine of us from five different countries seeing Cambodia for the first time. Seeing and living were very different from reading, watching and listening in comfortable homes and lecture halls. Things taken for granted at home were not easily achievable here: clean water, sanitation, sewage management, waste management and education, just to name a few.

We were lucky to have people with many different backgrounds: industrial and strategic design, architecture, urban planning and landscape architecture, which enabled each of us to focus on a few topics to develop deep insight so that we could help others see problems from various perspectives while working in teams. Nightly briefings kept everyone clued in and these discussions were very fertile. We were also lucky to have students from different parts of the world in the course, as well as working with Cambodian students during our stay, which made the whole visit fluent and fruitful. Soon we’ll return to Helsinki and form groups with those who did not travel, expanding the diverse set of perspectives even more.

We are free to choose a site for our studio projects. Among the most terrible of the relocation sites was Trapieng Krasang, where the urban poor from four different places were involuntarily relocated to some 20kms outside the city and they now struggle to survive. This is a population of Tuk-Tuk drivers, Moto-Dub drivers, bakers, street fruit vendors, waiters and waitresses who have been relocated away from their jobs and now have no income. One lady, for example, makes two and a half dollars a day if she goes to the city to sell vegetables. However, it costs two dollars to get to the city! The relocated families were each given nothing but a 5 by 12 meter plot on a former rice field. The earth is fertile there, but the plot is far too small to be the source of living, let alone the money to build a shelter.

Empty plots in Trapieng Krasang. Many of the evicted families sold the plots for very cheap price and headed back to the city slums due to the lack of job opportunity. Sold plots have become the subject of speculation, which will make the rich richer.

This is compounded by the issue of unclear entitlements, which dates back to the Khmer Rouge regime when many citizens were herded out of the city. One third were killed and many of the survivors never returned. Eventually, those who did return to the city settled wherever they could – with whatever means they could. A few decades later, the Cambodian government, challenged with deep-rooted corruption, is selling the prime locations of Phnom Penh city to private investors who are taking advantage of murky land ownership status.

Development in the city of Phnom Penh is another significant problem. Two years back, a private investor bought the Boeung Kak Lake area which is about 1 square kilometer and began filling in the lake to build a hotel and resort. People near the lake have been forcibly relocated and a large fire during our stay in Phnom Penh cost hundreds of families their homes in a single night. Now Boeung Kak Lake is as small as one third and soon will be 10 per cent of its original size. As summer brings monsoon season we will see the impact of the such radical environmental changes. Recently the Royal University of Fine Art as well as the National Museum have been sold to a private investor and the students are under threat of eviction.

![Boeung Kak lake as of March 2010.

Photo credit: Save Boeung Kak Campaign [http://saveboeungkak.wordpress.com]](../peoplepods/files/images/383.540.jpg)

Boeung Kak lake as of March 2010.

Photo credit: Save Boeung Kak Campaign [http://saveboeungkak.wordpress.com]

Some can say that development in Phnom Penh is giving jobs to construction workers, hopefully boosting the economy, and making the city a better place to live in the end. However, the number of the people evicted from the city is much higher than the number of workers hired. Does development have to be at the expense of so many homes, jobs, and lives lost?

The economy of urban poor in Phnom Penh is shallow and fragile: many of their livelihoods are very much dependent on tourism, a competitive industry with significant competition from nearby Bangkok. Cambodia imports many things, including foodstuffs, from Thailand and Vietnam, thus making commodities expensive. The shift from agrarian to industrial society, then an industrial, and on to a service and knowledge-based economy appears to be a long journey for Cambodia.

City in Crisis course does not pretend that problems of this nature can be mitigated immediately. Rather, it aims to have us students aware of and ready for the real problems of architecture and design for a longer term.

Back in Helsinki, we’re focusing on five different projects: a master plan including urban farming solutions for the relocation sites, in particular Trapieng Krasang as a case study; a “sub-center” concept for relocation sites, which brings markets and basic facilities to the area; the rehabilitation of remaining lake areas south of Phnom Penh, with specific attention to management of sewage flow; disaster management for slum inhabitants; and finally mine, a strategic road map and a framework for the economical development of the urban poor of Cambodia.

My question started from the living condition of Trapieng Krasang but my interest has soon extended to the economy of urban poor and the mindset: what does a pathway to economic stability look like for the relocated families of Trapieng Krasang?

I’m Seungho Lee, a Masters student at Aalto University School of Art and Design, studying in Industrial and Strategic Design and currently working with Helsinki Design Lab as an intern. My studies have taken me to Cambodia, where Aalto University's City in Crisis course is expanding the design discourse to include history, corruption, land entitlement, education, political enfranchisement, economics and more. This post was written a while ago, and it's part one of three covering my studies in the City in Crisis course.

As I type this, I’m 8000km away from home, waiting for a return flight from Phnom Penh, Cambodia back to Helsinki. I’ve been here for two weeks with nine of my fellow students as part of the City in Crisis course. Although I came to the airport three and a half hours early, I don’t mind because I wanted to escape from the city: there’s been a lot to digest after two quick weeks of fieldwork.

During that time we’ve been visiting Angkor Wat, the floating village near Siem Reap, Silk Island, a few slum areas and few eviction sites in Phnom Penh as well as relocation sites where those evicted now struggle to survive. We've also met and learned from representatives from various NGOs: STT, OPC, UN Habitat to name a few. Corruption, lack of secure tenure, almost no industry, false development, lack of education, slavery… this is the reality for many of Cambodia’s urban poor.

Floating village, a vernacular principle in Cambodia where the rainy season continues for six months.

Architects in the wealthy parts of the world have a tendency of being primarily interested in what their more successful counterparts in other wealthy parts of the world are busy with. The professional magazines in Europe, North America and the rich parts of Asia are concentrating on the “wow-factor” and its various manifestations. It is far less common that these publications deal with the everyday problems of the majority of the world’s problem.

– Hennu Kjisik, Veikko Vasko, & Hunphrey Kalanje. The Final Report of City in Crisis, May 2009

This phenomena is evident in recently published Phaidon Atlas of Contemporary Architecture that introduces 16 Finnish projects among 588 European projects, but only 26 projects from whole Africa and 184 projects from Asia. As pointed out by Hunphrey Kalanje, one of teachers of the course, architecture is in many cases political: it works with capital, for capital, and by capital.

The City in Crisis course has been offered since 1993 by the department of architecture in Aalto University School of Science and Technology with an aim of strengthening the global awareness and social conscience of its students, as well as increasing our understanding of the realities of life and conditions of professional work in developing countries.

Since these things are notoriously difficult to be taught in lecture halls and studios, the annual fieldwork period has become an essential part of the teaching and learning process since the beginning. After a total of ten years in Africa - Rusfisque, Benin and Grand Popo in particular - City in Crisis has turned its eyes to the east, and the first group of students traveled to Cambodia at the end of February 2008.

Some of my fellow students in the heart of Angkor Wat. One can easily imagine how glorious the Khmer civilization once had been.

The course is designed in two parts: the first of which aims to acquaint its students with various development issues all over the world and local vernacular principles. During the autumn semester in 2009, we read about and studied about four themes: development discourse, global issues, urban agendas, and construction in developing economies, which was followed by research into the vernacular principles of indigenous architecture in different climates.

The second part consists of lectures and seminars dedicated to issues in Cambodia, the fieldwork to Phnom Penh and Siem Reap and eventually the studio work back in Helsinki. From January of this year invited lecturers have talked about issues in relation with water, development, corruption, environmental issues, capital, and speculation in Phnom Penh.

After studying these issues from a range of scales, both from the global to the local in Cambodia, and from the past to the present we packed our bags for two weeks in Cambodia. It was time to see and to “live” the reality.

Check in tomorrow for more about our time in Cambodia.

There are few places that could serve as a better platform for a discussion about architecture and the city than the roof of a skyscraper, smack in the center of Los Angeles. Last week Postopolis! LA convened a group of more than 40+ speakers for five days of near-constant conversation. I was pleased to be able to participate by sharing the story of Helsinki Design Lab 1968, a bit about where we're going with HDL 2010, and to introduce the Low2No competition that Sitra recently launched.

Photo from Storefront for Art & Architecture on Flickr.

It was great to see some old friends and meet many new ones, but I particularly want to highlight the way that Postopolis! LA came to be. On this blog we've been describing different kinds of innovation, and Postopolis! is no exception. Unlike most events which have a central organizer, Postopolis! was hosted by six bloggers from five different cities, all enabled and made fluid through online collaboration tools. Think about that for a minute. The images and ideas from Eric Rodenbeck's presentation about data visualization, Benjamin Ball's design by process, and Ben Cerveny's thought-wander through the territory of the city as operating system will be playing on repeat in my head for a long while, but the quiet triumph of Postopolis! LA was its own formatting – the very nature of the event as a unique collaboration might just be the most impressive part of all. (This may mean we have too much event-planning on the brain...)

Now that we're all back to Helsinki to rest up and let these experiences soak in, this blog will probably be a bit slow for a while. In the mean time, you can browse the Twitter stream from Postopolis for extensive notes, excerpts, and the occasional dérive.

Is political protest a relic of the 20th century? In a way, this is the question that The Hope Institute asks here in Seoul. As a non-profit that runs a number of different advocacy and education programs, the Hope Institute proposes that "social invention" can replace protest as an effective tool for improving the quality of daily life. Over the past two years they've collected more than 16,000 ideas and are actively prototyping some of them.

In some of their most interesting work the Hope Institute uses crowdsourcing to collect ideas that can improve various aspects of living in Korea, from tweaks to the Metro system to alternate farming practices. After collecting advice from the people on the ground, Hope Institute brings together various stakeholders (be they government, business, or other communities) to join in one conversation about the problem at hand and then prototypes solutions and publishes their findings.

Photo from Arne Hendriks on Flickr.

One ambitious project they're working on is to change the visual experience of Korea's busy streets. With little regulation applying to the way that signs and advertisements are applied to building facades, the streets can quickly become a cacophony of sales pitches. Hope Institute's "Sign is Design" program hosts the municipal offices in charge of signage, the sign owners, and the sign designers in a single conversation so that all parties can work together to find a more orderly and pleasing way to deal with signage. Recently they adopted one of the rundown streets in Busan's old city center and applied their process to redo the all of the signs. If this were all for the sake of a more beautiful street we could note its improvement briefly, but post-renovation shop owners have noted that foot traffic and sales are both up. This increase in business is the direct outcome of good design being applied to a problem at all levels, from the strategy of bringing together all the stakeholders down to the graphic design of the individual signs.

If you speak Korean you may enjoy watching this presentation by Hong Ilpyo from LIFT ASIA '08, Research Fellow at the Hope Institute, where he talks about more of Hope Institute's work. The Q&A is in English and starts about 15 minutes in.

From the top of the ArcoTower in Anyang, a town in the southern reaches of the Seoul metropolitan area, it was quite clear what happens when a functionalist approach is taken to urban design: you get a city comprised of rubber stamp blocks, each the result of some generic equation optimized for things like "habitation units" and traffic flows. Top down planning can be quite efficient and was an important tool in South Korea's rapid urbanization in the latter half of the 20th century, but while growth rates may change quickly, concrete stays put much longer. In other words, buildings and cities planned with only the near future in mind may be immediate successes, but can quickly morph into liabilities when looked at over the span of multiple generations.

Photo: Anyang, South Korea photographed by Yong27 on Flickr.

Mr. Ohn Yeong-Te, President of the Architectue & Urban Research Institute (AURI), crystalized the problem that architects face when trying to improve the quality of the built environment by stating that designers are responsible to three parties: the people who live their daily lives in and around buildings, the businesses which rely on the smooth function of the city and its structures to ply their trade, and broader society which deserves high quality architecture that may become "tomorrow's cultural heritage." These different levels of responsibility relate to various strata of decision making from the grass roots all the way up to national policy. Without a perspective that incorporates design input at all levels of decision making it's very difficult to deliver high quality buildings.

This eloquent description of a need for planning that is integrated and informed from top to bottom was further expanded upon by Cho Sang-Kyu, Manager of AURI's Architecture and Urban Information Center, who described the need for architects to collaborate horizontally across disciplines. As society puts increasing demands on our buildings (it must be green! it should sustain itself financially!) the architect finds that they must work directly with other disciplines to deliver the informed perspective that is required of them.

Although AURI's work is at the national level (they report to the Parliament of South Korea), Anyang was the perfect place for this discussion about the potential of design-informed decision to result in high quality spaces. With iniatives like the Anyang Public Art Project, the city itself is actively looking for solutions to the rubber-stamp urbanism they've inheretied from the mass-production past.

Later in the day, a visit to the buzzing offices of Cho Minsuk, Principal of Mass Studies, provided some context to the discussion at AURI. Where are the precedents for this kind of integrated thinking amongst the community of designers? I'll sign off now with this as an open question to you: Which architects and designers are finding clever ways to insert themselves into these larger questions? Who do you look to for role models in this area?

On our last day of meetings in Bangalore, we had the pleasure to visit Srishti School of Art, Design, and Technology where Geetha Narayanan shared with us a bit of the history of her ground-breaking school and some of the opportunities and challenges facing educators working in India today. Geetha and her team have built a wonderful momentum within their school which has grown from an inaugural class of one single student in 1996 to an enrollment of over 250 today.

A theme that comes up again and again as we visit educators in different countries is the need for designers to be better trained to operate outside the bubble of art and design. It was great to hear Geetha flesh out the term "design education" beyond the training of designers to include something akin to the concept of the embedded designer I described previously. With the collaborative, studio-style approach gaining popularity in all levels of education from primary up through grad school, it's exciting to note that these students are learning new ways to think about and see the world in addition to the content of their various subjects.

To imagine that a pedagogy which uses design to helps students better understand the world could be taking root in one of the planet's most populous countries is an exciting proposition indeed. Being here for a few days has given us time to get only the smallest peek into life in India, but it was enough time to clarify how great the opportunities are for even the smallest of innovations in a place as vast, populous, and talent-filled as this.

I’m on my way to a meeting, so forgive me for the haste with which I jot down the start of an idea (I’ll expand later, but this is too important to start later).

We had an inspirational morning in Bangalore today. One of them was with Poonam Bir Kasturi and her team at the Daily Dump project. This is an amazing project driven by a critical issue: Sustainability. While the term is growing with “cult-like” popularity, most of the airtime being given is from a 30,000 feet perspective. Poonam’s team is deeply rooted in the complexity of the problem as it confronts daily life. The focus is on waste, tackling it from a composting perspective through a systematic design approach that is rooted in meaning, culture and economic realities. This is not a “deep dive” into the problem, but rather a powerful example of how design is being applied to create real social innovation by re-designing its value chain (sorry, I hate this business term, but you get what I mean).

Over a wonderful lunch, we discussed many issues primarily focusing on design innovation, the team’s “subversive” way of redefining problem boundaries, and culture…. seems like our discussions, almost without exception, end with the question of culture.

I have many thoughts racing through my mind as I realize my growing skepticism for what I would call “board room innovation”. Back on this topic and Poonam’s work shortly…