Competencies

This might be the most common question we've received lately, so as we prepare to close out HDL and this blog we want to share some thoughts on the subject. Below I dip into the weeds a bit with some macro thoughts on social change but, if you can stick with it, I do actually answer the question eventually.

Organizations, like Sitra, think about the world and the impact they want to create, which is usually expressed in a mission statement. This describes the world we would like to see. On a more frequent basis we define strategies that represent our best guess about how we will most likely be able to achieve the impact we believe is important.

And while these missions and strategies may be well formulated, they do not always necessarily match up with society. Indeed, a good bit of the value of an independent organization like Sitra is that it has the mandate and resources to think about things which are not on the top of society's mind right this moment.

But this also creates a challenge: Sitra represents approximately 120 out of the 5.4 million people who live in Finland. How do the actions of 0.0022% of a country create meaningful change?

Organizations like ours often try to push society. We prepare reports and studies that compile the facts, and those facts in turn lay out a case for change. By launching programmes and initiatives we attempt to push individuals and other organizations to behave differently—to seek different outcomes.

With the HDL projects we've been testing a different approach, one that works by pulling individuals and organizations towards our vision. In a time of low signal-to-noise ratio—when there's lots of noise—being smart and having the facts is not enough. We also have to provide an offering that is so compelling, perhaps even seductive, that it can attract attention and interest of collaborators.

Push makes sense when you know exactly what the market wants (be it a literal market or a 'market of ideas'). Pull makes sense in a more dynamic context, or when cash and/or authority are limited.

When we think about social change through the lens of push and pull, I offer the anti-smoking campaigns of 20th century as an example of push. Reducing the prevalence of smoking in society was a massive effort that was not aligned with the popular culture and media of the time, it also ran counter to the interests of some large corporations. There was significant inertia that resisted a specific and desired change: namely lowered tobacco usage rates. Affecting this change required prolonged effort on behalf of countless organizations. The movement had to be created more or less from scratch. Societies across the western world and beyond were literally pushed towards a different baseline behavior: from smoking as an acceptable norm to a default of non-smoking in many places.

To understand social change through pull, Facebook offers a good example. The world's largest social network is used by over one billion people and as much as the platform itself is a piece of technology, that technology has begun to change the world around it. Facebook affects how people convene for events, celebrate birthdays, spread gossip, and, according to the NSA in the US, how terrorism operates. All of this has happened relatively quickly and with very little money spent on attracting attention through traditional means such as marketing—Facebook did not grow through a push strategy. Instead Facebook offered something that was so attractive it pulled people in.

Without trying to valorize a particular company, what we've taken from this observation is a recognition of the competitive landscape that good ideas have to survive today. Good ideas are not enough anymore. Rarely does any one group have enough money to push ideas into the world anymore; rarely does any one group have the requisite authority to create meaningful social change by fiat.

HDL does not have the means to affect change on its own. Sitra does not have the means to affect change alone. The whole of Finland does not have the means when we think about the large scale issues such as climate! Therefore our projects have been an experiment in pulling participants, collaborators, and onlookers into projects. We pursued a pull strategy because it gave us a plausible way to leverage deeper flows of change within Finnish society.

Back to the original question: how did HDL select its projects?

The answer is that we looked for opportunities that lay between the vision that Sitra has for Finland's future and the interests of Finnish society right now. Within that opportunistic space the real challenge is not identifying a potential area or subject to work on, but to find the vehicle of change that has a high possibility of success.

A concrete example is Low2No. Sitra's interest in sustainable well-being means that we will need to address many (if not most) aspects of our economy and how we live together on a finite planet. Citymaking, the focus of Low2No, is as good of a place to start as any! We had indications that a project focusing on sustainable city making was well-timed to pull interest from the communities of development, real estate, construction, and design in Finland. When we began Low2No we were also considering a relocation of the Sitra office, so this also gave us the opportunity to address multiple needs at the same time, and for our organization to have some skin in the game.

Open Kitchen provides another example. Although Open Kitchen is ostensibly about food in Helsinki, our motivations were in addressing the sustainability of consumer choices in Finland (starting with diet), strengthening everyday entrepreneurism, and in creating proactive opportunities for new generations of immigrants to knit themselves—and be knitted—into Finnish society. Those same goals could have been addressed with a project that focused on groceries instead of street food, or even a focus-area that has nothing to do food, such as small retail shops. The reason we chose food is because there was already an existing groundswell of interest in food thanks to the successful Ravintolapäivä festival.

The project was Open Kitchen because food was a hot topic in Finnish society and our agnosticism about the content allowed us to connect our strategic goals to a variety of potential vehicles. If cycling were the thing, or meanwhile usage of spaces, or pop-up shops, or childcare, or energy, or anything else were the hot topic we would have developed Open Cycling, Open Spaces, Open Shops, etc. instead, leveraging the interest of the community. These stand a better chance to pull in the attention of finnish society, saving us from the need to create attention and interest in our subject, before we can even begin to generate interest in our project, before we can even hope to have a successful project.

How did HDL select its projects? By looking for opportunities where we could inflect existing energy within Finnish society towards the strategic priorities of Sitra and our assessment of what will be critical for Finland's vitality in the future. The financiers aren't the only ones who can enjoy the benefits of leverage.

For more on choosing vehicles for change, see the introduction chapter to Legible Practises. Readers may also enjoy a brief discussion of using projects and publications as probes to help discover opportunity.

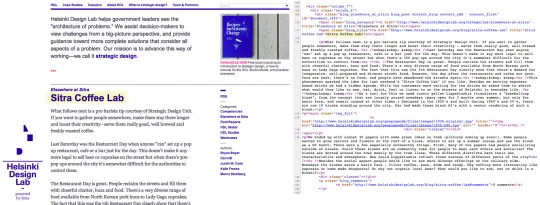

While booting up HDL we took some time to build out the infrastructure for our future work. A central part was this website, helsinkidesignlab.org. We've already shared some of the statistics, so this post details how the website came to be and what we were thinking about when we created it.

Have a clear goal

Our goal with the site was to be "a place for designers to come together to learn more about strategic design and participate in the conversation. The HDL site also needs to serve as a resource to government officials, providing information on what strategic design is and how it can help solve their problems."

Make the goal dead simple

We wanted to be the best, clearest, and most dependable resource for information at the intersection of design and government. The primary content we would share is the story of our own evolving work. Secondarily we would highlight the work of others through cases and blog posts.

Get help

Through various engagements over the span of a few months we worked with BERG London to define the strategy for HDL's website; Brain Traffic to edit and hone the message, tone and voice of our core documents (more on this below); TwoPoints to establish a visual language; and XOXCO and Rumors to manifest all of this as the website you're now reading.

The website was my project and prior to HDL I'd spent years working in pretty much every role involved in creating a website, from programming to journalism. So I felt prepared to handle the project, and I also felt strongly that it was important to get help and make sure that the site was done right.

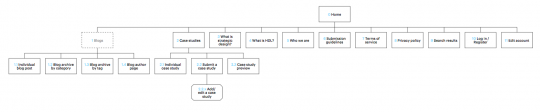

An example from Rumor's work on the information architecture of the site. They started by thinking through the structure of the site before anything was ever designed.

Be conscious of your audience

In a dream world we wanted to be relevant to everyone. Who wouldn't love strategic design?! We prioritized our audiences up front: other designers would be the first, followed closely by civil servants and politicians, and we wanted our materials to be accessible to interested laypeople.

This is the work of content strategy. Get someone smart like Brain Traffic to help you with it. Here's a snippet from their recommendations:

Tone and voice

Because the subject matter is a bit complex and conceptual, clearly clarifying who you are and what you do is important. Your site needs to sound academic, authoritative, and forward-thinking, yet still accessible and personal. Also, because your site operates similar to a non-profit, it should not sound commercial, because you are not selling a specific product or service.

Core messages

These are some core messages your site should convey:

1. Through strategic design, we offer new ways to solve large-scale, global problems.

2. We bring government and design together.

3. We want to advance the strategic design community.

4. We define problems and help deliver more complete solutions.

5. We take the principles of traditional design and apply them in new ways to "big picture" challenges.

Be realistic about the size of the audience

We anticipated that our audience would be relatively small. The percentage of the web audience that is interested in design is small, and strategic design much much smaller. But that's OK: While we have a small audience, they're generally quite committed—and thirsty for camaraderie and content. Building a website for an audience in the thousands is different from working on a website for the hundreds of thousands or millions. For instance, we opted not to invest in building some kind of social network (despite the desire for connectivity) and instead put our focus on publishing content.

A slow website is a nonexistent website

The web is a firehose of content. Lots of it is bad. While it would be nice to imagine that the good stuff will shine through, there's also a basic battle for attention. If you don't post, you don't exist.

We made a commitment early on to post regularly (in the form of weeknotes). This forced us into the habit of regularly documenting what we're doing, and also ensured that there was a steady stream of content on the site. This way the site would not feel abandoned or stale.

Banners? We don't need no stinking Banners!

As a non-commercial site we're able to free ourselves from the clutter that is imposed on most commercial sites by virtue of their banner ads. Helsinkidesignlab.org has a lot of white space on purpose: we want our readers to have a sense of clarity and focus when visiting the site. We don't need banners, so why have them?

Painless posting

Regular posts would not be easy to imagine without a painless interface for posting new content. Although off-the-shelf systems such as Wordpress are cheap, they can also be ill-fitted to specific situations and clumsy to use. We opted to build our own custom content management system using XOXCO's PeoplePods platform.

Editors' note: In writing Legible Practises we told the stories of six teams working towards systemic change in their communities, organizations, and institutions. In the book you will find our perspective. Below you will find a personal perspective from Rodrigo Araya Dujisin, who played a key role in the Constitucion case study.

—

Hybrid forums are a tool for balancing the knowledge and interests of different stakeholders, particularly when addressing a controversial subject. The design of the Hybird Forum carefully sets aside hierarchies so that ideas and controversies can be debated more openly and productively. The goal of a Hybrid Forum is to reach agreements on difficult subjects, by establishing shared responsibility for decisions and co-designing mutually agreeable outcomes.

The Hybrid Forum seeks to even out the asymmetries of power by equally valuing different forms of knowledge, perspectives and interests. Rather than smoothing over differences or seeking to eliminate them, the methodological challenge of the Hybrid Forum is use the existence of difference to spark the exchange of knowledge and collective decision-making.

Hybrid forums are spaces where the socio-technical controversies caused by specific overflows take the stage in a more or less institutional way, with the participation of the concerned stakeholders on the one hand and scientists and experts on the other. They are spaces that allow problems to emerge that experts do not see, to reconfigure problems that have already been identified and to create a world that is common to all participants, which must always be open to new explorations and learning processes. The hybrid forum is the creation (artificially, if you like) of relatively symmetrical conditions for dialogue, meaning that it is fundamental to destabilize the unquestionable everyday hierarchies for it to work.

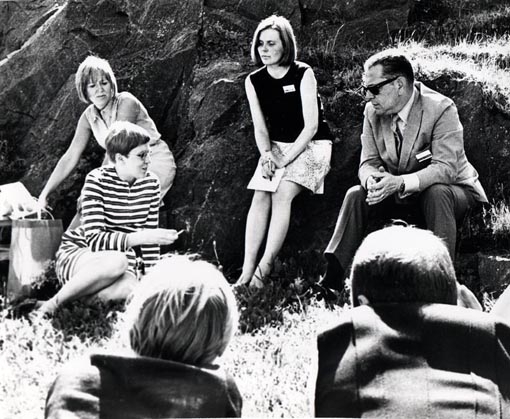

Rodrigo 'diving into controversy' during a Hybrid Forum as seen in the film Mauchos

1. “The one paying for the party does not choose the music”

The common good is the overriding goal and it should serve as the guiding principle for fostering dialogue and seeking consensus. While this may sound simple, in practice it is extremely complex to outline the common good among stakeholders who have different interests. On the contrary, it is very easy to appoint oneself the representative of the common good, but the commonality in such situations is rarely widespread.

While a single entity might fund a Hybrid Forum, their interests alone cannot drive the dialogue. Arauco, a company with interests in the city of Constitución, proposed and financed a new master plan after the city was ravaged by a tsunami in 2010. Tironi Asociados, along with a consortium of other actors, were asked to create an inclusive process that would give the citizens of the city a voice in its reconstruction. One of our first tasks was to convince Arauco that the plan had to be governed by a consortium that was representative of the city and whose members included the authorities, technical experts, companies and the community. At first they looked at us strangely—they were, after all paying, so shouldn’t Arauco have more say?—but they quickly understood the importance of this mandate.

Regardless of who pays, a new master plan would affect the lives of everyone in Constitución, so the governance of the project had to truly reflect the common good at stake. Though they might be the main financiers, it is not guaranteed that the project will be tailor-made to Arauco’s specifications. The one paying for the party does not necessarily choose the music. Both Arauco as well as Codelco, the main promoters of the aforementioned plans, agreed to form a board where the cities’ different stakeholders were represented.

This implies that subjects which are difficult for the funder may emerge during the discussions. For example, in Constitución there was debate in a public forum on the very presence of the Arauco cellulose plant in the city. The controversy was put in the public spotlight in a straightforward way. The main complaint against the plant has to do with the bad smell it produces in the city. While some people proposed removing it from the city, others defended its presence as a source of jobs; the company presented an improvement plan to integrate it into the city better. Arauco emerged from this forum with the commitment upgrade their plant through an investment of approximately $6 million USD. Human odor testers were proposed as part of a community monitoring system, complementing scientific monitoring of the perceived odors.

Producing this type of decision requires putting the common good first, which is beyond the grasp of any one stakeholder. The city itself is the guarantor of the common good and the city consists in all of its dimensions: authorities, experts, businesspeople and citizens. The Hybrid Forum becomes an ad-hoc town square meeting, a democracy, a miniature universe.

—

2. Dive into the controversy

To deploy a conversation on a citywide level you need to seek and to identify the key voices. In addition to the most obvious authorities, leaders and stakeholders, it is important to identify the critical voices, the informal leaders: to represent all possible worlds.

Ethnographic immersion such as this requires the wisdom of a craftsman, the precision of an acupuncturist and Buddhist patience. Getting to know the little stories and characters is fundamental to building bridges, facilitating dialogue, forging consensus and cobbling decisions together.

This implies getting to know the different stakeholders, the big and small discussions, the tensions, and the conflicts in the city. It means engaging both the powerful and the marginal sectors. One must immerse themselves into the city and its many communities in an ethnographic way, seeking to understand them on their own terms.

It comes through having a lot of coffees, sharing many beers, and listening. For example, shortly after starting work in Constitución, we found ourselves in a slightly depressing dark room taking with leaders of the local chapter of the Communist Party, a traditional and respected organization, but one that is very marginal when it comes to the decision-making process in an already marginal city. That night we asked ourselves: What are we doing here? That night we met people who ended up being fundamental to forging agreements on the Master Plan. Our team felt the same way as we met with 14-year-olds, young surfers, street vendors and the local aristocracy. It’s impossible to know a priori who will have the missing pieces of the story that become essential at a later date.

—

3. The Open House

Through practice we learned that the Hybrid Forum works best when it has a physical home in the heart of the city. We call this the Open House. The Open House becomes a symbol of the process itself, while also serving as an operations center for participation. This is where the forums, councils and meetings are held.

We installed the Open House in the main square of Constitución, in her geographic and symbolic center. This might appear to be a frivolous detail, but it was extremely important to process because the Open House is a place that is born without the preexisting valences of public spaces, including municipal and hotel halls or organizational headquarters. As a new place, the Open House is gradually filled with meanings and contents as the participation process progresses. As a neutral space, the community’s trust can be built from a neutral starting point and does not need to overcome past connotations or legacies.

The Open House team must include an appropriate mix of locals and outsiders. Especially in a small town, the outsiders give the process a special touch, as they are not “the same people as always.” The locals give the process social pertinence, in addition to the social networks required for meaningful deployment in the local community.

—

4. The forum as a network: Composition and structure

Upon convening the Open House everything learned in the previously has to be applied with an acupuncturist's precision. The forums did not seek statistically perfect representation, but we were careful to meticulously watch out for the well-worn pathways of power that we had discovered during the early ethnographic immersion. Forums have to reproduce the complexity of a territory; the different social worlds. The forum’s composition is fundamental.

We are not interested in having 1,000 or 5,000 people at a forum if they are homogeneous. We seek a heterogeneous network with a high degree of intermediation. That is, a capacity to build mediating bridges between different social worlds. In network theory this is known as "betweenness." We had authorities, engineers, members of the military, priests, teenagers, radical environmentalists, communists and businesspeople at the hybrid forums in Constitución, a network with the capacity to "infect," to disseminate the conversation throughout the city.

The objective is to have all of the stakeholders, visions and interests on the issue at stake available. If the controversy is the oasis of the desert-city Calama, for example, then farmers, real estate developers, indigenous people, the municipality and businesses with interests in the territory should participate. The friction begins with all the actors at the table and a proposal as a starting point. Hybrid forums open up hidden tensions and conflicts. They are made explicit; all elements are put on the table and a persistent attempt is made to find common ground. This is sometimes a consensus and at other times it is not, but that does not paralyze the process. The parties stake out their positions, but they also leave room for agreements

—

5. Catharsis and overflows

These are processes full of friction, conflict and uncertainty. Hydbrid forums should allow collective catharsis to occur. The mere fact of bringing together diverse stakeholders is an opening for the otherwise-contained tensions to emerge, the scores yet to be settled, the historic demands to be voiced once again. Our experience indicates that it is positive to let this tension be expressed, as a hard fact, and to consider it as a starting point. The worst thing is to ignore them and to rush the search for solutions and consensus.

Catharses are small crises and they are not easy to manage. There is always the temptation to take the moral high ground and to question the other side's legitimacy. This is where facilitation is fundamental for channeling the catharsis from the emotional plane (anger, indignation, feelings of injustice) to the philosophical one (ontological pluralism, accepting the other), followed by the socio-technical plane (consensus, proposals).

We have witnessed all types of catharsis. One of the hardest moments we faced was a four hour confrontation in the Open House, with TV cameras and digital streaming, where people held the company financing the plan responsible for the last 100 years of failures to fulfill promises, frustrations, and damages. In our attempts to move from the emotional to the ontological (everybody deserves respect, everybody makes mistakes, everybody can improve), a person took the microphone and, visibly moved, said that the forum was very difficult to participate in because it was like bringing a rapist and his victim together in a mediation room. The brutality of the metaphor produced a long silence without anybody refuting the premises behind it, not even the company. After a long and uncomfortable silence all sides agreed to try it, to use dialogue to seek a world in common for the future, in this case planning the city. Catharsis is the best investment (of time and emotional energy) for a fruitful dialogue.

—

6. Material dialogue

Engaging in dialogue is a real art, but it can be a nightmare if there is not a concrete subject, issue or controversy. The dialogue at the center of a Hybrid Forum is particularly difficult because it involves participation on the part of actors with different knowledge, biographies, levels of education and interests. To hold productive dialogues it is fundamental that the conversation be given materiality through proposals and conceptualizations that synthesize information, layers, points of view. The more visual and concrete these can be the more effective they will be.

Hybrid forums deal with a specific problem based on a proposal made by an expert team. The rules of the game establish that the proposal can just be questioned or improved, but also that the question itself, the premises, can be changed as well, with the possibility of opening up new questions and new controversies.

We refer to materiality in two ways. First, we refer to the synthesis of information in the form of a PowerPoint presentation, a model, images, graphics that ground the verbalization of proposals in additional media. Second, these slides refer to works, concrete projects that the city wants to implement. This allows grandiose statements like "safety is important" to become embodied in a specific decision that has material consequences.

The materiality for dialogue has two main objectives: to produce dialogues with focus and, second, to democratize or to socialize expert knowledge, valuing other types of knowledge. In other words, it is about producing epistemological symmetry. In general experts hide in their little worlds, protected by their own language, and jealously defend their quotas of power. In hybrid forums they have to validate their expertise with all types of audience. Their credentials are left out of the argument.

This is where wonderful interactions are produced, such as between a PhD in oceanography and a fisherman, between a transport engineer and a taxi driver, an urban developer and a street vendor, and all of this with bureaucrats, business executives and local artists mixed in.

So, what connects this whole mosaic of knowledges, whose interests are confronted on an everyday basis, who use their quotas of power and hold conversations among the deaf? We believe that materiality contributes to producing the grout that holds the mosaic together.

—

7. Sportsmanship and Ontological pluralism

To avoid conversations among the deaf, where each voice tries to impose its perspective, and to avoid instrumental dialogues where each stakeholders comes into the game with a shopping list, there is a need to learn (and to teach) how to deliberate with a sportsmanlike attitude, with fair play. This is almost a form of collective therapy.

There are two fundamental rules here: a sportsmanlike spirit and ontological pluralism. The former refers to being willing to lose something, to taking on more flexible positions to reach what Bruno Latour calls "a world in common."

Ontological pluralism refers to acceptance of the "other" in his full complexity, with his virtues and defects. It will be hard for authentic dialogue to take place if one stakeholder discredits or negates the position and interests of the other. In our everyday lives we use caricatures and simplifications of reality and for a hybrid dialogue there is a need to question and to take apart said simplifications.

If a businessperson calls an environmentalist an "eco-terrorist" or if the businessperson is called a "thief," then the existence of the other is being denied. How can such caricatures be taken apart, at least for the purposes of the Forum? The answer is: with patience, with many one-on-one conversations and with a great deal of frankness on the part of the facilitator during the hybrid forums. The benefits are not long in coming and the diverse stakeholders let down their guards and open themselves up to dialogue with the "other."

Skillful facilitation is fundamental. Dialogue often rises in tone, the parties get passionate. The facilitator holds a position that is different to that of all the other parties, including the experts, but it is not a neutral one. The facilitator is the one who guides the dialogue and gradually brings the common ground between the different parties to light. They must protect the deployment of dialogue, gradually sketching out the areas of agreement and prioritizing the public good. To achieve this, the must have an active voice and often say no to demands that are beyond the real possibilities of the forum (change authorities, certain rules, etc). The facilitator must keep the forum’s focus on shared problems, avoiding the possibility of getting caught up in private concerns.

All of this is aimed at creating a conversation by converting technical proposals owned by experts into social questions owned by the community. Accepting tensions and conflicts builds the openness and flexibility needed to gradually reformulate the technical proposals.

—

8. Socio-technical craftsmanship

Forging a world in common is a craftsman's job. It is about intertwining the social, the technical and the political. It is about assembling collective decisions, weaving together ties between people, mixing the emotional and the rational; creating new truths.

It is the work of a craftsman because it requires managing the conversation in its full complexity, with personal tensions, parallel agendas and multiple pressures. It is the work of a craftsman and also high tech, because it uses all devices and dialogue platforms.

We get worried when easy agreements emerge that could hide tensions that have not been dealt with. Tensions must be resolved in all dimensions: with experts, decision-makers, the affected parties, and the occasional curious person passing by the square.

In Constitución a well-known local businessman tried to forge an alliance with fishermen outside the forum, trying to create an bloc that would work against a key part of the master plan, as they would both face expropriation from their homes. Fishermen were initially very critical of a proposed tsunami mitigation park along the water, as it affected them directly. They argued that, in addition to being victims of the tsunami, they would now be the victims of reconstruction by being pushed further away from the shore. As the process went on, after tense dialogue sessions, they began to show their understanding and to accept the greater good that the proposal meant for the city. Acknowledging the "greater good" meant losing something very important to them, such as being located near to their boats, their jobs. Thus, we slowly and delicately outlined an agreement. The fishermen proposed two criteria: a) a fair relocation and, above all, b) for it to be democratic. If the poor had to go, then so did the rich people occupying the same waterfront, barely separated by a street. If these two criteria were fulfilled then they would support the anti-tsunami park.

The attempted "rebellion" led by the businessman was revealed in the forum itself by the people who said that they felt like they were under pressure and that they wanted to maintain the rules of the game, the fair play. The businessman defended himself; he had to open up the conversation with many witnesses, and finally stances became more flexible. During this forum, mathematical modeling was also presented to show the true mitigation of the proposed park, which ended up being quite high, with a 40% reduction of the wave speed by virtue of the friction introduced by a new forest. Urban planners had stressed the need for a great public space that the city did not have. The people themselves had proposed in the initial visioning workshops had said that the most important thing for them was the city's relationship with its natural environment. Others made comments full of emotion. All of this was in public: the science, the emotions, the legal restrictions, in an open house held in the town square and broadcast on local TV and with Internet streaming. A civic opera, crafted in common.

—

9. Communication without complexes

What happens in a hybrid forum is of interest to the entire city, which entails the challenge of bringing the hybrid forum to all corners of the city. To take that conversation to every bar, every family table, every street, communications play a fundamental role. They accompany the participation process and contribute to disseminating a narrative of the process, especially among more passive audiences.

Given the relevance of the process, documenting it is important. In this context, we have a variety of media - like documentary film - to document the path to controversy resolution and to provide a symbolic testimony of the community’s participation in its development. We use all forms of communication to inform, seduce, and convene the citizenry. Old and new communication technologies are used, from megaphones and pamphlets to digital media outlets, in addition to TV and the printed press. Everything goes when it comes to reaching broader audiences.

Summonses, progress, conclusions, agreements, disagreements and everything that happens in the participation process is communicated.

Between 50 and 100 people participated in the Constitución hybrid forums and between 500 and 1,000 people in an open town council meeting. Regardless of how well the forum has been put together, this is nevertheless a small number if we consider that decisions will be made that are of interest to an entire city whose population is above 30,000. Communications allow you to fulfill a maxim that se set ourselves: "Nobody can be allowed to say that they did not find out what was going on in the Open House."

—

10. The party, the hangover and starting over

Hybrid forums have the capacity to produce new agreements, some strong, some provisional; the world people have in common is outlined. The result of the forums is given back to the city. A public consultation process is held where the central decisions are subjected to a referendum and the people are asked to prioritize the different projects that comprise the overall plan.

The consultation is a democratic celebration. Reaching this point has already produced change in the city; the fact that proposals have been submitted that were elaborated by the different parties involved is something that generates trust, identification with the process—imperfections included—and it gives it an epic touch. The result: the city has a road map that reflects technical excellence and is economically and politically viable while enjoying social legitimacy.

But like all parties, then comes the hangover. In this case the hangover is the plan's implementation. If the sportsmanlike spirit is not maintained, then disagreements emerge when it comes time to implement the urban projects. Controversies are updated and new overflows are produced.

Outside of the walls of the Open House and beyond the bracketed time limit of the Hybrid Forums, the questions remains how this type of participation might be maintained over time and scaled up to broader levels of society. We do not have answers yet. The common world is still under construction.

—

For more, check out the relevant chapter in Legible Practises and read this conversation with Rodrigo on the Brickstarter site.

Editors' note: In writing Legible Practises we told the stories of six teams working towards systemic change in their communities, organizations, and institutions. In the book you will find our perspective. Below you will find a personal perspective from Corinne LeTourneau, who played a key role in the Brownsville case study.

—

The sense of excitement in the community center was palpable as a group of 200 people started chanting, “Where is HOPE? Inside Brownsville!” This was a landmark moment for the Brownsville Partnership, a community revitalization initiative spearheaded by Community Solutions. This display of enthusiasm took place at the conclusion of the Hope Summit, an event which kicked off a yearlong community planning process in partnership with community members, helping community members to work together to shift the conditions that perpetuate poverty in their neighborhood. The Hope Summit not only serves as an important mechanism for partnering with the community to formalize its vision, but also represents the culmination of years of patience and building trust with community members in the neighborhood of Brownsville.

Brownsville, Brooklyn is one of New York City’s most troubled neighborhoods. The vitals of Brownsville make for grim reading: poverty, crime, homelessness, unemployment, child welfare, education, and health. More than one-third of Brownsville families live below the poverty line, unemployment is higher than average, and 29% of the population left high school without a degree. In short, the community has struggled in recent years by almost every indicator. Community Solutions began working in Brownsville in 2005 and established the Brownsville Partnership in 2008 in hopes of making Brownsville a safer, healthier, more prosperous community.

We knew that we would need to earn the trust of the community if we hoped to make a difference. As outsiders we might be construed as ‘parachuting’ into the neighborhood if we did not place community partnership and engagement at the forefront of our goals. Thus, the newly formed Brownsville Partnership started seeking out neighborhood leaders for collaboration. This search quickly brought Community Solutions’ president, Rosanne Haggerty, and the BP team into contact with the unofficial mayor of Brownsville, Greg Jackson.

Jackson grew up in Brownsville, briefly played in the NBA, and returned to his community to run the Brownsville Recreation Center, one of the few strong community institutions at the time. Jackson was a trusted neighborhood leader who loved the “village” of Brownsville from his childhood and continually sought ways to help people see the hope inside Brownsville. Haggerty and Jackson hit it off immediately. Jackson was immediately drawn to Haggerty’s vision for neighborhood change and her desire to get things done. He sensed that Haggerty and her team were not going anywhere and they were in it for the long haul. In Jackson, we found someone who could bring local authenticity to the effort in a way no one else could.

Jackson’s enthusiasm led to him joining the BP as it’s first director. Together, Jackson, Haggerty, and the entire BP team recognized that they had to work at building trust every day in the community to convince a weary Brownsville neighborhood that we would not abandon them like many organizations had done before. This required a mix of both patience and urgency. It would take time for the community to be convinced that the BP could enable positive change, but we also needed to bring a sense of urgency to building widespread trust and social capital within the community. It soon became clear that for the community to trust in the BP, they needed to see evidence of change being possible.

Making visible change in response to residents’ concerns became a theme early on. For instance, in 2009 the community shared its concerns about the quality of food found in markets throughout the area. The BP immediately sought out a partnership with a farmer’s market operator to bring quality, healthy food into the community. By summer 2010, the farmer’s market stand launched and the quick response to the food needs and the visibility of the project proved to be a “trust multiplier”. Even community members who did not purchase produce at the market, still saw something different and positive in their community. This model of making visible things happen soon became an ethos when developing new projects or programs. New health programming was deployed in the form of neighborhood bike tours, walking groups, and visible wayfinding signage and maps to encourage walkability. Community meetings now took place on neighborhood corners and the farmer’s market expanded to two additional locations to increase the BP’s visibility. The community was beginning to believe change could happen; they could see it happening.

Our work also benefitted from the involvement of local residents, which helped us further strengthen the ties of trust. The BP invested in staff dedicated to community organizing, outreach, and mobilization. Our community mobilization team consists principally of residents who have successfully resolved their own past challenges with the help of the BP and now utilize their rich local networks to spread the word about the BP and encourage participation. Small, structured house meetings—"Coffee Klatches"—are often the vehicles for this process.

These house meetings serve as a means to listen to the community and hear their concerns, and also to develop achievable solutions in partnership with community members. For instance, community members expressed concern over the lack of activities for youth in Brownsville. The community mobilizing team then used additional "Coffee Klatches" to discuss solutions and launched a local youth resource fair. The community mobilization staff has also become ambassadors for the BP and represent the BP at community meetings and events.

Investing in these staff members assists the BP with sustaining trust and hope in Brownsville by building a permanent, seven day a week presence in the community and creating a continuous feedback loop for community concerns. Having a deep connection to the local context enables the community organizing team to help the BP understand the specific needs of specific people within the neighborhood, thus enabling us to develop initiatives that respond to the actual context of residents lives and meet the needs of real people.

For more about Brownsville, check out the relevant chapter in Legible Practises!

In the design world there's an obsession with "representation," or the act of representing ideas and concepts in media (be it a poster, a book, or a building). In part this obsession stems from the recognition that an idea in your head is only as useful or as interesting as your ability to articulate it in a way that can be shared with others (in whatever medium suits you and them). How you present your thinking matters. But the term designers use is is "represent", not "present." The former shyly evokes two important relationships: one in time and one scalar.

To "re-present" an idea is to perform its meaning anew. Expressing something in new ways, perhaps unexpected ways, has the potential to help us refine the very thought that we were trying to express in the first place. This is the essence of "talking through" a notion: making successive attempts to explain something helps clarify the thing itself. Representing ideas is not frivolous, it's essential. Representation helps us understand the essence of what we are trying to share.

But "representation" is also important in the realm of political science, where it implies that an elected official represents the interests of their constituents. This is a scalar relationship where one vote effectively represents many, even if the many might each have their own variations if asked directly. Implicit in this one to many relationship is a basic fungibility: because it's impossible for one vote to capture all of the nuance of the many that it stands in for, there's always the possibility that the 'one' can change. The same can be said for any act of visual expression: when a book goes to press, for instance, the cover that is chosen is not some inherently perfect crystallization of the ideas, but it's the right expression at the moment a decision was made, for the people who made it. The selected expression sits at one terminus of a family tree of options (and families of options).

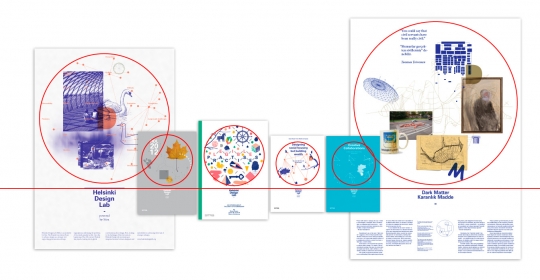

In the spirit of being concerned with representation in both senses of the word I thought it would be interesting to show some of the background thinking that went into the HDL brand itself. Before beginning work on the first HDL website, which would become the public face of our initiative, we invested some time (and a little money) into clarifying our visual language. To help us with this work we hired TwoPoints.net, a Barcelona-based graphic design firm who we've now had the pleasure of working with on multiple occasions over the past four or so years.

When I met with them in their small studio we started from zero. What is strategic design? Having arrived on an overnight flight from California, I was speaking in the weird metaphors that proper jetlag inspires. They giggled when I described strategic design as being concerned with "hairy problems". Even still, Martin and Lupi try to sneak this into our collaborations.

But no, it's not as literal as a hairy McNugget (though that would be problematic). By hairy I meant to imply that the sorts of issues we're concerned with are unclear, they're ambiguous, fuzzy, in motion, and often just hard to grapple with. In short, they're difficult.

The second starting point was the legacy of HDL itself. We had just recently discovereda wealth of photographs and other documents hiding in the archives. In 1968 the first HDL-related event was stylish, but because of its era it was also very paired back, appearing almost minimal to today's eyes. We wanted to evoke this and connect with the lineage of our thinking.

Photos: Kristian Runeberg

Third is the nature of Sitra itself. As an organization that reports to Parliament, Sitra is a serious institution, and our design-related work is no exception. We asked TwoPoints to respect the seriousness of work we were setting out to do by giving it a downplayed visual expression. The result, as you will see, if a visual language that can be rather austere in its most basic applications. We've carefully avoided graphic frills over the years. We've embraced the blank space, the negative space.

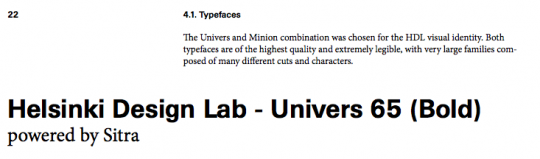

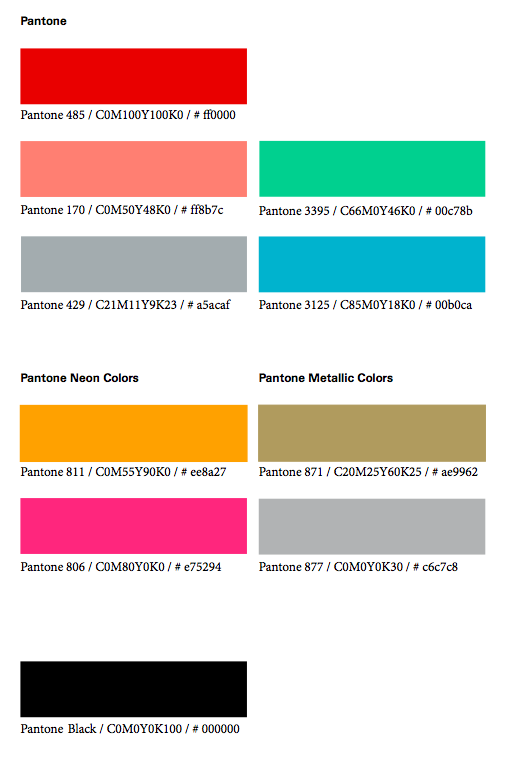

After our first meeting Lupi and Martin spent a couple weeks digesting the contents along with Irene Hwang of Constructing Communication, who was also contributing to the project. We asked them to provide us with a style guide that defined a visual language for HDL, including all of the basic such as typography, colors, and a family of layout concepts (expressed as common grids that we use in all documents).

When they finally came back to us, their document, a styleguide for HDL, opened with this:

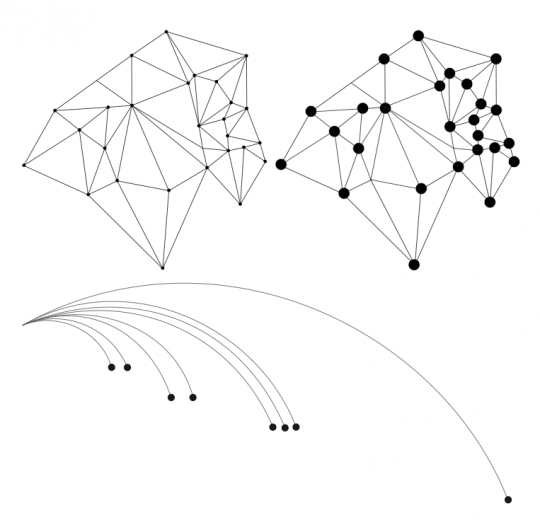

The driving idea of the visual identity is drawn from the “space” occupied by the strategic framework of HDL, which draws together a diverse group of actors and entities from various fields. These actors, each one a specialist in his field, contributes a unique point of view within a group that can offer a more holistic definition of the problem, thereby creating the opportunity for a more effective range of solutions.

Here you can see the genome of our Studio Model already emerging. The general notion of a collaborative, multidisciplinary, design-led framework is certainly at the core of the Studio, but it's also true of our work in general. So how to express this visually?

In terms of visual representation, this space is filled by heterogeneous visual styles that serve to represent the actors with different backgrounds functioning in a holistic way.

The conceptual framework of this particular visual identity, in contrast to a “normal” branding, avoids homogeneity or uniformity in favor of highly diverse visual styles occupying the same space. Yet, given this embrace of heterogeneity, the visual identity maintains a sense of stability in order that the identity expresses trust, confidence and recognizability.

Thus, the visual identity is both flexible and constant. The identity contains two zones: 1) A flexible image space that may house corporate elements or images that illustrate a specific content and 2) The wordmark space. On the following pages we will outline the different applications of the word- and imagemark.

Facing the challenge of representing HDL as an entity that would constantly evolve as we collaborated with different actors and entities, TwoPoints chose to eschew a static logo and instead designed a visual system that is flexible, yet in all of its iterations remains recognizable.

The system is comprised of five key elements:

1. HDL elements. Shapes abstracted from the letter forms of 'HDL'. We always use at least one.

2. Colors. We are relentless in using HDL blue (Pantone 072 or RGB(0,0,120) for the curious) if you haven't noticed, and that's thanks an initial decision up front that we would use 'blueprint blue' in all of our work. The other colors are used for accent.

3. Network elements. These imply connectivity, intersection.

4. A 'composition zone' defined as a space to be filled with image and typography depending on the application.

5. Grid logic. Basic rules about how to handle negative space keep the logo system from feeling cramped to squashed.

6. Typography. Univers for headlines, Minion for pretty much everything else. No frills.

This set of guidelines provides the building blocks needed to construct a wide range of documents and other visualizations. By spending the time to think about the visual expression—the brand—of our work up front we were able to move quickly at later stages. New publications, new documents, new projects didn't bear the burden of starting from scratch, but they were also not overly-constrained. We had enough freedom to produce a variety of visual expressions that hung together as a family, while each having their own character.

We put this much effort into the visual language of our initiative because that was one low-hanging fruit of differentiation. As newcomers to the market of ideas in 2009-2010 we felt that we would have to stake a claim for ourselves, and while there are a wide variety of very smart people saying and writing very smart things in the communities of social innovation, sustainability, government reform, and the others that we've traveled in, the level of visual sophistication was somewhat lacking.

The ideas are what matter in the end, and I hope the value of our work is determined by the value of nothing other than our thinking and execution. The time we spent on the visual expression of HDL was our way of imbuing what we do with a great deal of care, and in doing so respecting the time and attention that you've given us.

Talking to students recently I was asked "what do you really do?" A lot of the work is setting conditions and context so that people can do their thing. Most often this means getting contracts right so that collaborations can set off without friction. Briefings are also of critical importance.

Another big part of what our team does is give expression to things that are otherwise invisible. We do this so that these unseen aspects can become part of our conscious decision-making, and so we can tell stories that help others broaden their decision-making.

Showing our work is not always easy, or at least not in a way that makes it interesting. What we do usually invovles people sitting in a room talking. Sometimes they stand up. Occasionally they scribble things on a whiteboard. So how do you show this in a compelling way—in a way that someone who wasn't there might actually want to pay attention to, and might actually glean something from?

In the spirit of legible practice below you will find the briefing that we sent to the photographer before HDL 2012. To see the outcomes of this brief interpeted by Johannes Romppanen a skillful photographer, you can check our gallery on Flickr or check here.

All shot suggestions are indicative rather than directives. In other words, they are to convey a sense of the 'story' we want to tell with the images, and I leave it up to you to stick to these suggestions where it makes sense, and contradict when you have a better idea.

+++

THURSDAY 11th @ Helsinki Contemporary Gallery / Bulevardi 10

Best if you can come at the end of dinner, so that we can give people a head's up. Also good for them to get to know each other before being photographed.

We will begin dinner around 19:30-20:00. I propose that I text you when we are finishing mains and then you can come over.

1. GALLERY SEEN FROM AFAR. Perhaps from inside the park. A dark frame with a bright gallery in the middle, small but obviously alive.

2. PEOPLE! AT DINNER! Not sure how to do this, but maybe easiest if we actually get everyone to toast or something.

3. AFTERMATH. Either literally after everyone has left and the table is still set up with napkins on the floor and tipped over glasses and whatever, or perhaps when people are still around but done eating. Messier the better.

FRIDAY 12th @ Pajasali Suomenlinna

1. WALKING THROUGH KAUPPATORI. Our guests amidst the hustle and bustle, either as a string of people walking together, or as individuals. As if you were spying.

2. BOAT: People getting on, sitting and talking. A shot looking back towards city center, with people in foreground if they're out there, otherwise part of the boat in the frame so it's clear that you're not on an island, but actively in transit. Akin to:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/helsinkidesignlab/4968866663/in/set-72157624904191894

3. SETTING. Some shots that establish the scene, the location, which may or may not have people in them. The entry to Pajasali is a small door on a massive facade, so it's nice to see small people in contrast to the structure. Possibly shots of the meeting happening, but seem from the outside, through the glass.

4. EVENT: Probably best if you sit for a while without taking any photos to let people get used to you being there. But use your judgement. No special directives here, but some shots of people discussing.

5. RING OF CHAIRS. We will have the chairs in a circle. Try to get a shot with the whole ring visible. Otherwise, please grab a series of shots that we can stitch together (I can do it so you're not bothered). This is a theme from last time:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/helsinkidesignlab/4970979696/in/set-72157624904191894/

6. PEOPLE STEALING A MOMENT AWAY: as individuals, pairs, or small groups, people will inevitably sneak away from the main part of the group to discuss something, have a phone call, etc. These are nice moment because they show a bit of humanity. The event is not consuming them. Example: http://www.archdaily.com/141823/mckinsey-company-hong-kong-office-oma/_mg_0127/

7. PROGRAMME BOOKLET: A shot of the book (ideally cover visible) in someone's hand, or just sitting somewhere. But an image of the book. Example: http://www.flickr.com/photos/helsinkidesignlab/6205412773/in/photostream

8. FOOD: food is very important to us because it's a natural opportunity to talk to new people, or change the conversation. So somehow to show that while people are eating, or grabbing food, they are also still "working".

+++

In 1968 Sitra had a design event on Suomenlinna, so this is a bit of a homecoming. Here are the photos from that. They're pretty amazing.

Photos from a previous event that we like:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/helsinkidesignlab/4968872519/in/set-72157624904191894

http://www.flickr.com/photos/helsinkidesignlab/4968684851/in/set-72157624904191894

http://www.flickr.com/photos/helsinkidesignlab/4969305960/in/set-72157624904191894

http://www.flickr.com/photos/helsinkidesignlab/4968855619/in/set-72157624904191894

http://www.flickr.com/photos/helsinkidesignlab/4970368253/in/set-72157624904191894/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/helsinkidesignlab/5032513281/in/set-72157624904191894

http://www.flickr.com/photos/helsinkidesignlab/5032520997/in/set-72157624904191894

http://www.flickr.com/photos/helsinkidesignlab/5033150866/in/set-72157624904191894

http://www.flickr.com/photos/helsinkidesignlab/5032536739/in/set-72157624904191894

http://www.flickr.com/photos/helsinkidesignlab/5032533765/in/set-72157624904191894

And something random but nice:

http://www.kinfolkmag.com/storage/journal/091912foodrenaissance/food-renaissance-2.jpg

In the grand scheme of our work, photography briefings are not among the most critical things that we do. But given that this was sitting in my email and it might be of use to someone somewhere I figured, why not, let's see what the internet finds to do with this.

Last week we finally went live with Open Kitchen. I'll let Antto explain it briefly and if you want more detail you should check the site; this post will focus more on how we ended up with Open Kitchen as a project.

Readers of this blog will know that we like our food, but the motivations for this project go well beyond the desire to get a decent falafel, banh mi, or reindeer sausage in Helsinki. We engage food because we're interested in broadening sustainable consumer choices and fostering social diversity within Finland. Food is a good way to address these topics because it's the original social object. It's a familiar, tangible, and inescapable thing that's deeply tangled in individual preference, shared culture, and dark matter. This is a familiar story, so I wont belabor it. Instead, I'd like to share some of the backstory to the project and use it as an example of the pivot—a play that we've been adapting from the world of startups into our public sector practice.

To plan is to change your business, to pivot is to let your business change you. Despite best efforts to analyze and plan, the world does not always play out according to the script we write for it. In these situations, where you find yourself standing before unexpected opportunity or pitfalls, to pivot is to change the means that you're using to achieve the ends you desire. After a pivot you're headed in a new direction, but still rooted in the same first principles.

One year ago, when we began working on what has now become Open Kitchen, the concept looked like this:

Belly First Sustainability (Food, Public Debate, Business) — Concept Note

We want to accelerate the development of the sustainable food industry and culture in Finland by incubating the Low2No service partnership in anticipation of 2013. The aim is to sell sustainability, one bite at a time.

This is accomplished by building a Sustainable Grilli in Helsinki during the WDC2012 to create an accessible and first-hand entry point to public debate about sustainable lifestyles in Finland. The project is executed in three components: a competition, a temporary food cart business, and an events programme (in Helsinki and other cities) concurrent with the business.

In this draft (from September 15, 2011) you can see that the emphasis is split between providing a platform to prototype part of Low2No and larger systemic change goals around sustainable food. The means we had settled on to achieve this goal was to create and operate a sustainable grilli kioski for the summer.

Between the first conversations Justin and I had about 'belly first sustainability' and writing this concept note, two important things happened: the Camionette and Ravintolapäivä. Both of these unexpected events changed the context of food and food culture in Helsinki, and more importantly they provided tangible evidence of a new group of self-starters. Both involved demonstrations of what that new culture looks like, how it tastes, and how it changes the experience of the city in ways beyond just the foods on offer.

This is a snap of Koepala, a popup during Helsinki Design Week. New food-related concepts are popping up all the time now. Open Kitchen is designed to help them take root.

Both also highlighted problems in public sector decision making. The silos of our regulatory context were not set up to handle initiatives that came in the 'shape' of a food truck or a create-you-own-restaurant festival. The result was some rather public shaming of various public bodies through traditional and social media when those institutions did their normal, conservative thing. To their credit these same organizations responded quickly and positively, but not very coherently.

The "shape" of the city's organization doesn't match the interests and experiments of the citizens—here the Camionette. So when something like a food cart first comes along as a question, public bodies can be caught off guard.

It literally doesn't fit into the silos that the city is organized around.

As we were working the concept note through various parts of the internal machinery of Sitra we were gleefully watching these changes happening on the street. And then something funny happened: we realized that we were developing a project for a world that didn't exist anymore. By the autumn of 2011 Helsinki didn't need a demonstration that sustainable street food was viable. That had been done already by entrepreneurs like Tio Tikka and activists like Olli Sirén.

Yet despite the positive blips that we observed, it remained difficult to get started in sustainable food in Helsinki. There was (and still is) a gap between the effervescent vitality of Restaurant Day and the day after restaurant day, when all of that surplus energy, excitement, and talent subsides back into previous routines. The ladder of innovation is missing some rungs, you might say. Restaurant day is a great way to test out an idea, but for those few who want to go further, where next? What steps exist between a pop-up and taking out a lease on 200 square meters of restaurant real estate?

These missing rungs of the ladder became our focus. We pivoted from a sustainable grilli demonstrating a new food culture, to a dark matter academy that could illuminate the tacit knowledge of sustainable food pioneers in Finland. We want to make it easier to create lasting, thriving sustainable food businesses in Finland. Open Kitchen relies on people who've "been there, done that" to share their knowledge and experience with others.

While this was unfolding we were writing the story, quite literally, in the form of a print-on-demand book. The research that went into the book and early development of the concept led us to meeting people all over the city, from restauranteurs to regulators to politicians, and everyone in between. We wrote it because that was an easy way to send us careening into the thick of things. Rather than sit in Sitra HQ and try to abstractly reason a view of the world, we got out there and started asking people how their corner of it works—or doesn't. Consistent across these meetings was a feeling that there's a good bit of knowledge and experience in the city, but it remains caught in pools—dark pools—within isolated communities.

Amidst our first proper blizzard of the 2011-2012 winter, Dan and I paid a visit to Ville Relander, who heads up Food Strategy for the City of Helsinki, and Elina Forss of Marrot Oy at the newly opened offices of Tukkutori. As we explained our interest in food the conversation fell quickly into a productive rhythm. Marrot, with the support of Ville and others, had been developing Kellohalli as a food culture hub for the city. It was to feature a strong programme of events, a library, and other activities. As strong as the plan was, it still pointed to the missing rungs of the ladder: once people get excited about food, what next? How do you go from enthusiast to entrepreneur?

The idea of the dark matter academy that we had been simmering (sorry!) was suddenly congruent with an opportunity right in front of us, with real names and availability and interest. That was that. In Marrot we had found partners who were already well positioned to help us develop and execute the concept of the dark matter academy for sustainable food. The pivot happened immediately, almost without a thought, because in fact the thinking had already been done and we merely catching up to the full implications of our intentions.

Pivoting can be difficult to accept, especially inside an organization that is used to a linear sequence from scoping to planning to execution to measurement. One of the ways that we try to deal with this is to focus on establishing the first principles of a project early on, revisit them often, and always explain our projects by building upwards from those principles. It leads to a bit of a broken record syndrome, but the best way to make sure the principles of a project are carried with the work itself is to repeat them over and over again—to yourself, and to everyone you're working with. This prepares us to make on-the-spot project decisions based on those principles, to align what we do with what we think, even in the smallest details.

Here, once again, we find that a useful play such as pivoting requires the right culture. Had any of the people in the team been rigidly locked into the grilli as The Thing To Do, or had the internal Sitra procedures rejected the Open Kitchen proposal, the attempt to pivot would have broken the project instead.

During the past week or so we've been hosted visitors from three continents who are curious about strategic design at Sitra. In each of these discussions we've touched on something that we call "legible practice". I first used the term on this blog less than a year ago, but it worked its way into our daily vocabulary somewhat before that. We use it as a way to split hairs with all the hype around "openness". Open data, open innovation, etc.

At risk of sounding arch, "legibility" has become a core notion of how we think about innovation, or perhaps more specifically public innovation, and this post is an attempt to define the term and describe its value. Very simply, doing things in the open is not the best way to help them grow. To encourage scale, we must do work in ways that are inviting, easily read, and digestible.

Let's hop back to 1994.

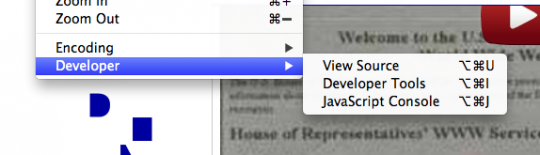

The world wide web used to be a very different place. Much of what's available on this website was not possible twenty-some years ago. Few people knew how to make websites in 1994, and there were certainly no schools graduating students who were versed in the subject. Most people learned like I did, from a friend who taught them the basics of HTML and showed them the most important command in the history of the internet: view source.

"View Source" is a command that lets you see the code that makes a webpage work. This is unique to the web—your word processor, for instance, does not allow you to see the source code that makes it tick. That's proprietary code (unless it's open source).

Left: our website. Right: a portion of the code you will see if you view source. I've highlighted a bit of text in both so you can see how one connects to the other.

But the ability to see the web page and the code that manifests it has been built into web browsers since the early days, and liberal use of the command is an invaluable tool for self-learning. HTML is a simple language, so as long as one can access the source code they can usually 'read' it without too much pain. I don't know why someone decided to add "view source" as a feature of the web browser, but it facilitated the spread of knowledge about how to make web pages. Here we unearth the imperative for legible practice.

Not only was the web new and rapidly evolving, but since there was not an in-built stock of Web Experts the group of people who happened to find themselves as members of a community building the web—and simultaneously learning how to build it—were all coming from different backgrounds. A lot of them were computer scientists, but there were also bored architects, distracted social scientists, news junkies, eager business students, and probably more than a few video gamers. The sheer diversity of the community meant that tropes and models from any particular tradition of knowledge could not be relied upon. Tutorials and other learning resources tended towards a more general audience because the community itself was more general in composition. The knowledge base and the community were in flux.

Innovation is in a similar moment of rapid development. The View-source paradigm implies that the more a developing practice enables and supports self-learning, the quicker it can grow and spread despite having a diverse composition. If you want something to go viral, you have to think about how it spreads. Practices tend to be a fair bit more dry than your average animated gif meme, so those of us who are invested in spreading a way of working have to think extra carefully about how they spread. We try to bring this concern into the core of our work.

As a public institution we enjoy the ability to do just about everything in the open, free for others to pick up and build upon. This comes in small gestures, like making our publications available under a Creative Commons Share-Alike license, but openness is not enough. As we aspire to maintain a legible practice, we're in the habit of not just sharing our work, but sharing how and why we do things in a particular way.

To invoke a bit of an infinite loop, this post is an example of what I'm describing, as are the rest of the how-tos. And we're not alone. Friends at Government Digital Services in the UK are conducting their own legible practice, and we would be happy to have other examples posted as comments below.

Other examples include our book In Studio, which features documentation of three studios we hosted side-by-side with a thorough how-to; full documentation of the Low2No competition including brief, process, and outcomes; and the Brickstarter project blog, where we're documenting every aspect of the project's development.

In each instance we are attempting to take a step back from the work itself and describe how we approached the problem as well as the methods, tools, or techniques we used to address it. We do this as an invitation to engage in a discussion about the work and its practices. In an ideal world, everything we produce would come with a "view source" regardless of medium.

The reason that we invest time in sharing in a legible way is twofold. Primarily, we feel that it's important to reflect upon the practices that we're developing, especially at a moment like this where knowledge is productively fluid. Doing so helps us hone our skills. It makes us smarter. Second, making our work legible enhances the likelihood that it will be copied.

An innovation fund is only as useful as it's innovations are influential. And what better way to be influential than to be as easy to copy and build upon as possible? Besides, when we see someone pick up a bit of our work and use it in their own way, we benefit by having our thinking reflected back to us in new ways. When describing practices, that reflecting-back is exactly what scale looks like.

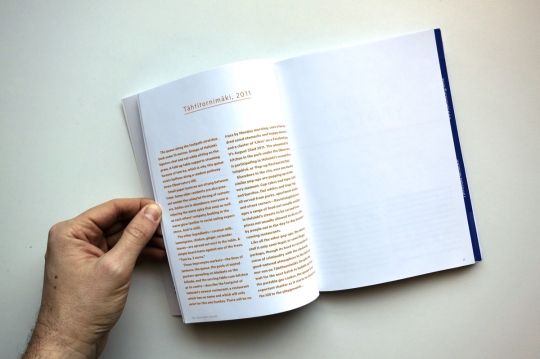

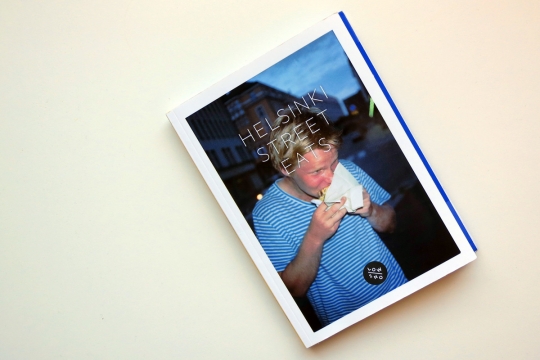

This post is part Low2No project update and part design how-to delving into simple customization of the Print On Demand books as a format. First, the update. Low2No is about creating pathways for our current, high carbon economy and culture to transition to a neutral carbon footprint. An important aspect of that is what and how we eat.

Especially for a place with the northern climate and high meat & dairy consumption habits of Finland, food production and consumption are key concerns when you're interested in carbon.

Helsinki Street Eats, a new book about street food as a vehicle for innovation

We've been looking at street eats as an example of "everyday food", the stuff that's close at hand such as late night snacks, kiosks, bakeries, food trucks, and the like. In fact, let's take a slightly modified excerpt from the Low2No site:

Street food describes systems of everyday life. In its sheer everydayness we discover attitudes to public space, cultural diversity, health, regulation and governance, our habits and rituals, logistics and waste, and more. What we find most interesting is the intersection of all of these aspects: how they come to a balance and tenor that enables and encourages specific kind of outcomes in a specific place and time.

Street food can be an integral part of our public life, our civic spaces, our streets, our neighbourhoods. Street food can help us articulate our own culture, as well as enriching it by absorbing diverse influences. And it can enable innovation at an accelerated pace by offering a lower-risk environment for experimentation.

Street food can do all of these things, but it doesn't necessarily.

This book is an attempt to unpack what's working and what isn't in Helsinki, and sketch out some trajectories as to where it could go next.

The full 98 page book is available for download, and you will also find links on that page to buy a printed copy from Lulu.com, a print-on-demand publishing service.

Readers of this blog may already know that we're a bit obsessed with formats. We are given to nerding out on the minutiae of publishing online and in print, which is probably no surprise since as a team we have direct experience in producing magazines, newspapers, books, radio, websites, buildings, and various other media. (Aside: this makes us an unusual public sector team, to say the least.)

It's nice to go all-in on a book and obsess over every tiny detail from writing to printing, as we did the In Studio: Recipes for Systemic Change. With this most recent publication on Street Food we were interested in exploring a format that would be more ephemeral. One that could change and evolve as our work on the topic does; a paper document that could have different version numbers; and one that felt easier and more casual. We also wanted to self-service distribution model.

Print-on-demand seemed to fit the bill, offering flexibility along most of those axes, but print-on-demand books tend to be… dull. The easiness of the format shines through. How could a print-on-demand book be a bit more special—could we find some relish to serve it up with?

People have been hacking print-on-demand to do some interesting stuff, but it seems to be all on the software side. We wanted to hack the print in print-on-demand. Lulu hacking.

Surprisingly, there still does not seem to be an option that surpasses Lulu. I say surprisingly because the Lulu experience is quite terrible. Their tools are limited and the workflow is awkward. As one small example, you can set the country of publication only after you've published a book. According to Lulu all published books apparently come from the United States, at least at first. Blurb is another popular print-on-demand service and their quality is higher, but their document sizes are limited and it's mostly for photo books.

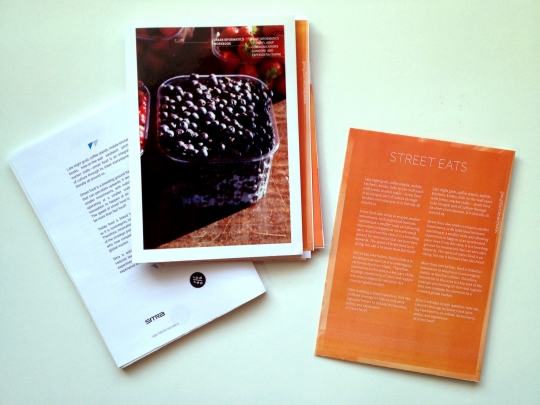

Over the past months Dan and I sketched lots of (sometimes ridiculous) ideas, including at one point the thought of laser cutting Lulu books into new shapes. Stepping back from that precipice, we've settled on a basic combination: a full-color 98 page print-on-demand book paired with an offset print fold-out poster, all bound together with a rubber band.

The books come straight from Lulu and the rubber bands can be found at any office supply shop and countless online sources so that only leaves the poster for us to source through a traditional print house.

Usually the spine of a print-on-demand book is a sore point because the alignment can be unpredictable. The rubber band nicely obscures alignment errors.

The poster is designed to fold down into A5 format so that it fits neatly within the book. Right now we're waiting for the actual posters to come back from the print house, but they will be printed on 60gsm paper which means they're a good 25% thinner than standard printer paper, making them easier to fold up.

Various paper prototypes using the office printer and tape to craft posters and an old Lulu book as a stand-in.

The binding pushes the poster out a few millimeters which creates a natural 'tab'. We discovered this on accident while making a prototype, but it was a nice discovery since we wanted to have a quick way to thumb to the Finnish language summary.

When we give out copies of the book they'll come with the poster and rubber band, but if you order a copy online or download the PDF you'll find the contents of the poster included as normal pages.

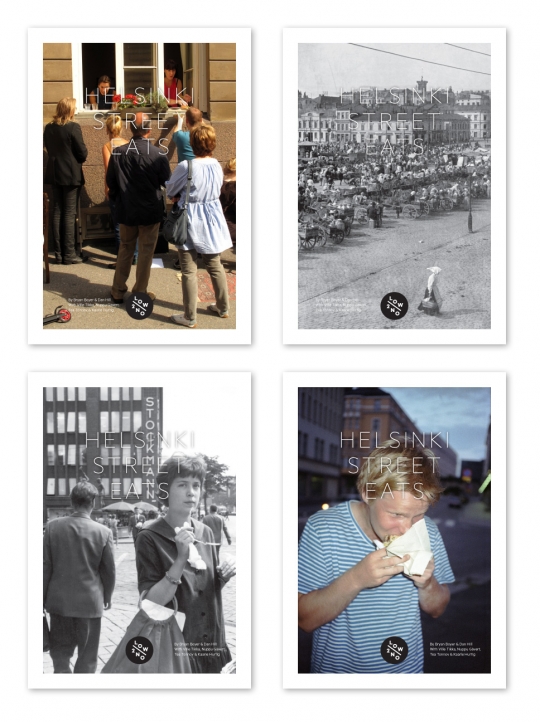

Because print-on-demand does not have any setup costs or minimum print runs, we can also offer the same book in multiple flavors. As we started working on the cover it was hard to settle on a single image, so we decided to let the user decide. There are four copies of the book available for download/print. All of the contents are the same, but you get to pick your own cover. My favorite features a scene of Kauppatori from 1901. What's yours?

Clockwise from top left: Ravintolapäivä August 21, 2011; 'The Great Saturday Market' at Kauppatori in 1901; Jaskan Grilli in August, 2011; Outside Stockmann in 1959.

Although the writing and research for this project has been on slow burn for about nine months now, the production of the book was pretty quick. Dan and I did all of the work in house, tossing files back and forth with occasional but insightful comments from Marco and Justin. One of the positive side effects of taking longer than expected to deliver this project was the opportunity to shoot extra photos around town, so it's richly illustrated.

The larger team included Ville and Nuppu of WeVolve on interviews and research; an investigation into the supply chain and geography of a typical hodari (hotdog) by Aalto University student Tea Tonnov; photography by the indefatigable Kaarle Hurtig; and tips and ciritique from too many people to mention.

Hope you enjoy! Hyvää ruokaa!

Note: This piece was originally written and published in OK Talk, a book produced by OK Do that is based on a series of conversations they organized around Europe. I'm sharing here because it dips into an essential question: what kinds of qualities should we look for in strategic designers?

If one visits a design book shop they are likely to walk away with an impression that these fields are becoming more and more embedded in work outside the usual cultural territory for which architects and designers are more commonly recognized. The politics of space, the economies of place, the sociology of material, and topics along these lines are increasingly the focus of publications. But is there practice to back up the rhetoric? Yes, some—but not enough of it.